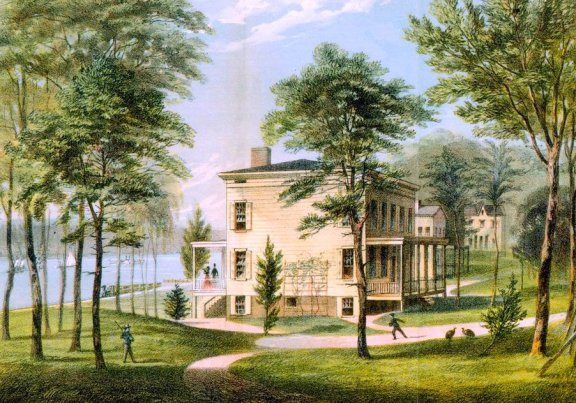

After a long and tumultuous career, naturalist John James Audubon sought a placid retreat in which to live out his final days. So it was that, in 1840, he purchased a large and heavily-wooded tract of land along the Hudson River between what are now 155th & 158th Streets. On it, he constructed a comfortable 3-story wood-framed house with an expansive porch overlooking the water, and named the estate “Minniesland” after his wife Lucy, whose nickname was Minnie.

When Audubon died at Minniesland in 1851, he left the estate to his wife. But this proved inadequate to provide for her, and she gradually began selling off parcels of land to keep up with her mortgage payments. Bit by bit, Minniesland disappeared until, in 1863, Lucy sold the house itself. The area, known for decades thereafter as simply “Audubon Park,” attracted the attention of railroad heir and philanthropist Archer M. Huntington. Beginning in 1904, Huntington snatched up parcel after parcel of Audubon Park with the intention of transforming it into a center of culture and learning.

Minniesland in the 1930s, shortly before it was demolished to make way for an apartment tower. Some records insist it was relocated for historical preservation, but proved too rotted to be saved. No solid evidence exists of its fate.

Huntington’s adopted mother was of Spanish descent, and his interest in her heritage drove him to found the Hispanic Society of America that same year. It would become the anchor of his new Audubon Park complex. As construction began on his new society’s headquarters and museum, Huntington gifted a parcel of adjacent land to the American Numismatic Society, of which he was a member. For its first half-century of existence, the society had floated from one rented space to another, lacking a permanent home. Huntington’s only stipulations regarding the land gift was that the Numismatic Society, which focused on the study of coins and medals, must begin construction within two years and maintain architectural harmony with his nearly-completed Beaux-Arts Hispanic Society building.

By December 1907, the Numismatic Society moved into its new headquarters next to the Hispanic Society, and the cultural center known as “Audubon Terrace” was born. By 1909, virtually all of the former Audubon Park had been absorbed by apartment development, as builders raced to meet the demands of Manhattan’s burgeoning population.

A NY Times article announcing the construction of the Numismatic Society’s headquarters, July 29, 1906

1911 saw the addition of the American Geographical Society to the Audubon Terrace cultural center. This society, founded in 1851, would aid President Wilson in his preparation for peace talks at Versailles during World War I.

Out Lady of Esperanza church as it appeared shortly after its consecration in 1912, with a grand terraced entrance off of 156th Street.

In 1912, Audubon Terrace acquired its own church, Our Lady of Esperanza. Fittingly for its adjacency to the Hispanic Society, the church was gifted a skylight, a lamp, and numerous stained-glass windows by King Alfonso III of Spain. The church, like the rest of Audubon Terrace, was originally perched high above 156th Street, reached by appropriately terraced staircases. The chapel was expanded, however, in 1924, and had its entrance lowered to street level.

The Hispanic Society (L) and Numismatic Society (R) as they appeared in 1908. The main entrance was then on 156th Street, seen in the foreground here.

Audubon Terrace reached its zenith in the 1920s, when the Museum of the American Indian (1922), the American Academy of Arts and Letters (1923), and the American Institute of Arts and Letters (1923) opened around the impressive plaza. Scattered among the museums and institutions were a collection of notable and beautiful sculptures and friezes, including an immense equestrian representation of El Cid by Archer Huntington’s wife, Anna Hyatt Huntington, which she completed in 1927.

The Museum of the American Indian as it appeared shortly after completion in the 1920s. (Courtesy of the NMAI)

In 1928, the Numismatic Society had outgrown its original building, and was granted permission to more than double its gallery space. Also, around this time, it was decided that the entrance to the Terrace should be moved from 156th Street to Broadway. Though this allowed the plaza to be fully enclosed and, therefore, more structural harmonious, it made the area decidedly uninviting to pedestrians.

A fully-enclosed Audubon Terrace as it appeared in 1988. The roof of Our Lady of Esperanza Church can be seen in the foreground. The wall to its left was formerly the 156th entrance to the Terrace. The famous Church of the Intercession and Trinity Graveyard, where Audubon is buried, are in the background.

By the 1930s, the area surrounding Audubon Terrace had become completely populated by immense and luxurious apartment towers, many of which had been built on speculation during the economic and population booms of the early twentieth century. The Depression, however, left the majority of these buildings sitting empty.

But political turmoil in Europe would lead to an influx of immigrants pouring into New York. And the empty towers of Washington Heights proved attractive to an immense population of German Jews looking to flee religious persecution under the newly-ordained Nazi party in their homeland. By the mid-1930s, more than 20,000 German Jews had settled in Washington Heights, earning it the affectionate moniker “Frankfurt on the Hudson.” This population would only grow as, in the aftermath of World War II’s horrors, thousands of European Jews and Holocaust survivors sought a community in booming postwar New York City.

The former Hebrew Tabernacle at 605 West 161st Street, constructed in 1922. The congregation moved north in 1973, and this former synagogue is now a Jehovah’s Witness hall.

But the fortunes of Washington Heights, and likewise of Audubon Terrace, were not destined to last. As Manhattan’s German Jewish population aged and followed nationwide migrations to the suburbs, Washington Heights’ hulking apartment blocks were again left empty and undesirable. Lowering rents attracted a fresh wave of immigrants, this time largely of Caribbean and Central American descent. And as New York’s crime levels spiked, the Heights were disproportionately affected. Drug use and associated crime overran this once-bucolic section of the island. Northern Manhattan became a no-go zone for New Yorkers and tourists alike. And the institutions who had stood so proudly atop Audubon Terrace for decades began to suffer in kind. Employees and members of the various societies were regularly mugged, robbed, and forced to witness any number of violent crimes.

Seeking safety and stability, Audubon Terrace’s members began fleeing the dangers of upper Manhattan. In the 1980s, the Museum of the American Indian moved into the former Customs Building near Battery Park. The American Geographical Society and the Institute of Arts and Letters shortly followed suit. In 2004, the Numismatic Society finally jumped ship, and it is now rumored that the Hispanic Society might also be looking to move downtown. Boricua College, a bi-lingual institution of higher learning, moved into the former Geographical Society building, but otherwise, the Terrace remains largely abandoned and overlooked.

The cultural complex and its surrounding neighborhood, named “The Audubon Terrace Historic District,” were designated a New York Historical Landmark in 1979. This will prevent any major changes to the buildings’ exteriors, but as the years continue to pass, the once-impressive plaza has begun to show its age badly. Moss sprouts between the cracked brick pavers, lamps sport broken light globes, when the post isn’t completely missing. Despite its very obvious potential, this once-grand cultural landmark is in desperate need of help.

Audubon Terrace as seen from above.

Rear L-R: American Society of Arts & Letters, Out Lady of Esperanza Church, El Cid statue & plaza, American Geographical Society (now Boricua College)

Front L-R: Institute of Arts & Letters, Numismatic Society, Hispanic Society, Museum of the American Indian

Walking around it today, I was overwhelmed by Audubon Terrace’s grandeur. As Washington Heights continues to transform and gentrify, I can only hope that fortune will again smile upon this relic of a more sophisticated age. The Numismatic Society’s halls would make a terrific events hall. The soaring walls of the Hispanic Society could host projected movies on Summer weekends, with concessions being sold in the Hispanic Society’s entrance hall. City College could rent classroom space, and professors could wax on about Spanish history int he shadow of Anna Hyatt Huntington’s statue of El Cid. These are glass-half-full daydreams of a naive historical optimist, I know. But one can hope that more lies in store for Audubon Terrace than a slow death of neglect and gravity.

I’m from Washington Heights and it history, please do not hesitate to post more about the heights, then.

Howdy, Neighbor! The Heights has such a rich and interesting history that most residents are hardly aware of! I’ll try to post more in the future and hope you enjoy it!